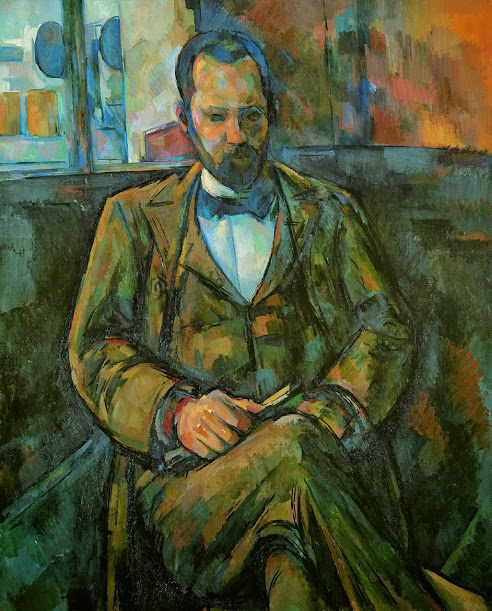

Even though Cézanne’s painting project was very different from Picasso’s, Cubist painters including Braque, Metzinger and Picasso himself all said that Cézanne’s work profoundly influenced them.

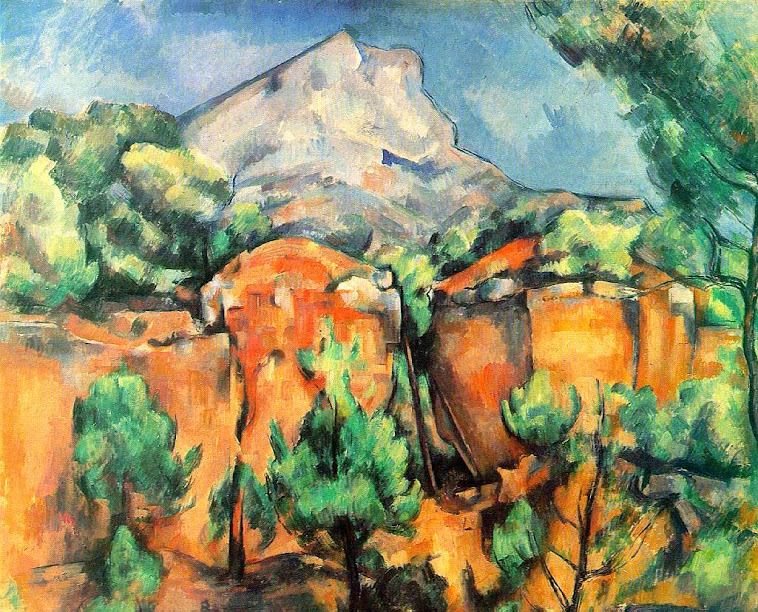

Paul Cézanne, Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from the Bibemus Quarry, c.1897, Baltimore Museum of Art

Paul Cézanne, Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from the Bibemus Quarry, c.1897, Baltimore Museum of Art

In fact, the painting that gave Cubism its name is directly connected to Cézanne, first through its title, as Cézanne often painted the small village called L’Estaque in the south of France, and then through its lines and colors, which strongly evoke Cézanne’s work.

Georges Braque, Houses at L’Estaque, 1908, Museum of Fine Arts, Bern

Georges Braque, Houses at L’Estaque, 1908, Museum of Fine Arts, Bern

Paul Cézanne, Bibemus Quarry, c.1895, Museum Folkwang, Essen

Paul Cézanne, Bibemus Quarry, c.1895, Museum Folkwang, Essen

Braque also painted this scene of L’Estaque, equally reminiscent of Cézanne:

Georges Braque, Viaduct at L’Estaque, 1908, Centre Pompidou, Paris

Georges Braque, Viaduct at L’Estaque, 1908, Centre Pompidou, Paris

The Cubist painters saw two key elements in Cézanne’s work, especially in his late paintings, which influenced them the most.

First, geometry.

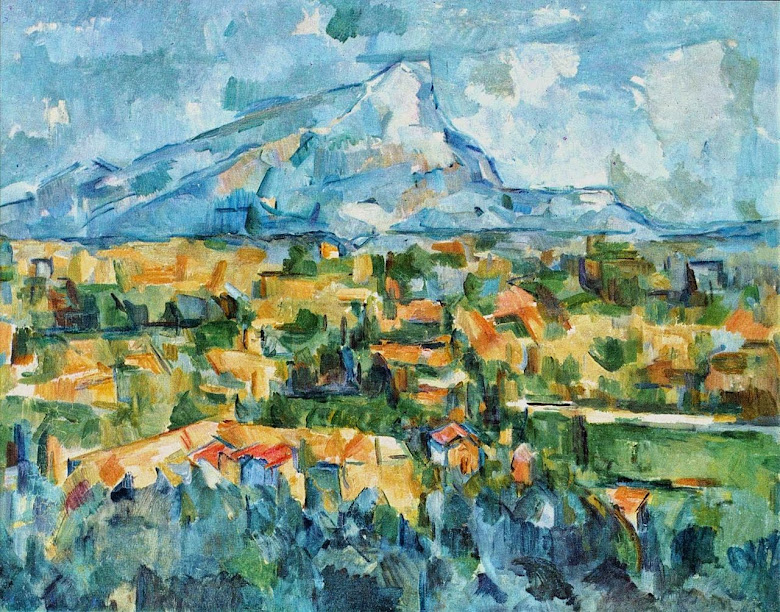

Paul Cézanne, Mont Sainte-Victoire, 1904, Philadelphia Museum of Art

Paul Cézanne, Mont Sainte-Victoire, 1904, Philadelphia Museum of Art

Paul Cézanne, The Grounds of the Château-Noir, c.1904, National Gallery, London

Paul Cézanne, The Grounds of the Château-Noir, c.1904, National Gallery, London

Even though Cézanne was mainly trying to create volume through color planes, the Cubists saw in Cézanne a tendency to represent nature with geometric shapes, which is central to the early development of Cubism.

Pablo Picasso, Brick Factory at Tortosa, 1909, Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg

Pablo Picasso, Brick Factory at Tortosa, 1909, Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg

The second element is perspective. In many paintings by Cézanne, it looks as if each object has its own independent space with its own point of view, which goes against the traditional single-point-of-view linear perspective introduced in the Renaissance.

Paul Cézanne, Still Life with Apples and Oranges, 1895-1900, Musée d’Orsay, Paris

Paul Cézanne, Still Life with Apples and Oranges, 1895-1900, Musée d’Orsay, Paris

The Cubists followed Cézanne in breaking the traditional rules of perspective, and then went further by introducing multiple views of the same subject from different perspectives at the same time, which is another feature of their style. A good example is the cup in this painting, seen both from the side and from the top:

Jean Metzinger, Tea Time (Woman with a Teaspoon), 1911, Philadelphia Museum of Art

Jean Metzinger, Tea Time (Woman with a Teaspoon), 1911, Philadelphia Museum of Art

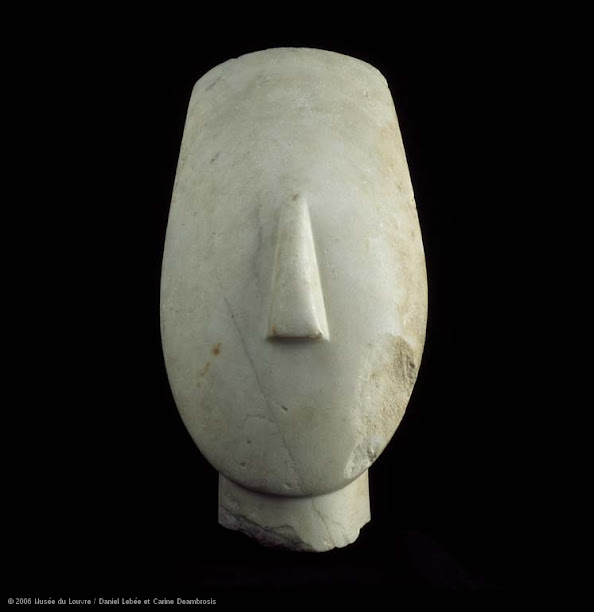

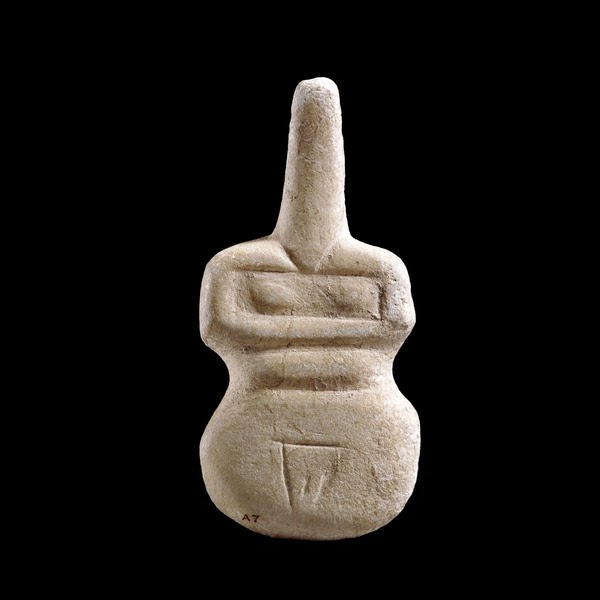

The development of Cubism was also inspired by other art forms, such as Cycladic art and African art, but Cézanne played a key role for Cubist painters, despite major differences in their approach to nature and painting.

Actually, Cézanne’s work was so influential that he has not only been called a father of Cubism, but also a father of modern art itself.